Experiences of expectations and well-being in Christian Church leadership

This is an adaptation of the report written about the research I conducted for my MSc and got a better mark than I thought! The original report had input from my supervisor Dr Eva Zysk and was written as if I was going to submit it to a journal. I've tweaked it so that hopefully you'll still get all of the good stuff, but with less of the fluffy, box ticking stuff. Thanks again if you took part in this and hopefully you can see parts of your thoughts reflected in my interpretations.

References are numbered and added at the end if you are interested in reading more.

Introduction

Well-being and leadership have attracted significant attention recently, with research being conducted into how we can define and create the best models for both. Leaders in any type of organisation form the foundation of its function and success, and well-being has been shown to have an influence on how leaders perform, and on their employees too (35). This applies to all types of organisation, from businesses, to health professions and to religious organisations. Church leaders oversee their congregations in a variety of ways; to teach, give truthful accounts of the doctrine, and direct or manage affairs (13). They are relied upon to keep the church healthy and grow the congregation. Recently, Christianity Today reported on the pressures and high expectations placed upon Church leaders, declaring a ‘burnout epidemic’ as hundreds stepped down from leadership (33). This research aimed to understand church leaders’ experiences of leadership, the pressures and expectations faced, and how their well-being is affected. Throughout, ‘the Church’ will be used to refer to the collective body of congregations within Christianity, and ‘church’ will be used when discussing an individual congregation.

Expectations of Church Leadership

Church Leadership expectations are intrinsically linked to Christian values. There are many teachings in the Bible which outline who a leader should be, what their character should be like and what they are to do. “Since an overseer manages God’s household, he must be blameless - not overbearing, not quick-tempered, not given to drunkenness, not violent, not pursuing dishonest gain. Rather, he must be hospitable, one who loves what is good, who is self-controlled, upright, holy and disciplined” (Titus 1: 7-8, NIV). This is also found in 1 Timothy chapter 3, which states both faithfulness and managing the family home as qualifications for leaders. Jesus also talked about leadership with his disciples, calling them to servant leadership: “Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be slave of all. For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve…” (Mark 10: 43-45, NIV). Underpinning these requirements for leadership are the commands to love the Lord with everything and love your neighbour as yourself (Matthew 22: 37-39), which are core values to the Christian faith.

These expectations go beyond the leadership role and characterise a way of life at home with the family, at work and engaging as a member of a church congregation. This makes leadership in the church different to working or volunteering as a leader in a charity or other job sector.

Within the Church of England (n.d.), other denominations and movements, a position of leadership is often achieved through exploring a calling, and growing gifts, which may be naturally apparent or spiritually given (13). It is expected that anyone who comes forward for leadership in the Church is a born-again Christian, one that has accepted Christ Jesus as personal Saviour. Unlike other organisations, such as Samaritans (2018) where volunteers are accepted “from all walks of life” (para. 15), leaders in the Church must demonstrate a commitment to the Christian faith through prayer, worship and discipleship (17; 13). Motivations for wanting to lead may come from wanting to please and serve God through serving His people, or from a desire to extend His Kingdom through teaching the Gospels and reaching out to the community (13). Some churches may expect a certain level of engagement before being considered, such as being a regular attendee, tithing a portion of income and being accountable through a small group and to senior leaders (30).

This extension of leadership as an act of faith and service is what makes Church leaders a unique group for research. Expectations for leadership are not confined to their role, but rather to a whole way of life, which could affect their well-being in a positive way by having a purpose in life, or negatively if there is tension in trying to live up to and maintain them. This could begin to explain why so many leaders seem to be stepping down due to burnout (33).

Burnout and Christian Leadership

Current research conducted among Church leadership has focused on burnout. Burnout is a multidimensional theory comprising three core components; emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced personal accomplishment (14). Emotional exhaustion is a lack of energy, and the individual being emotionally overextended. Depersonalisation develops in response to exhaustion and is a detachment from the job or others. Reduced personal accomplishment is a lowered sense of competency and inability to cope or to help others (14). Risk factors that have been identified in organisations fit into six main areas: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values (14; 15). Research by Maslach et al. (2008) suggests that it can be possible to identify early warning signs of burnout by measuring scores within these six areas. If warning signs can be spotted early, then it may be possible to intervene before burnout occurs.

Research has found that clergy might work with individuals with diverse needs ranging from grief and mental health issues to marital problems. They often exceeded a typical 40 hour working week (20; 6). This can increase the risk of burnout for leaders in the Church as they also face difficulties with demands on time and maintaining spiritual practices outside of ministry (5). Experiences of senior leaders in the Church suggest that an accumulation of other factors often contribute to burnout, such as taking on too much responsibility, conflict with others in the church and dealing with issues in their personal life (6). These examples given could fit into the burnout risk factors of workload and community, with potential overlap into the other four.

Further research suggests that engaging with certain practices can reduce the risk of burnout for senior leaders. These are for spiritual renewal and taking rest such as: daily prayer, having time to connect with God, and spending time with family and friends. Partaking in a combination of these practices seemed to enhance their mitigating effects, compared to practicing a singular activity. When leaders are challenged with the use of spare time for ministry, instead of rest or spiritual renewal, these preventative factors can be diminished and the risk of burnout increases (5; 10).

Burnout among senior leadership is an important area to investigate, including causes and possible preventative measures. However, churches are not just made up of the senior leadership and the congregation. Even within churches, there will be different levels of leadership such as associate pastors; ministry pastors for young people, children, worship and pastoral care; team leaders and week leaders, although terminology may vary depending on the church movement or denomination (31). Not all these different types of leaders may be paid in their leadership role nor do it full-time.

Many of these leadership roles are part-time and some leaders may have employment outside of the Church and lead in a voluntary capacity. For these leaders, time for spiritual renewal and rest outside of church leadership and other employment might be limited, particularly if they work shifts or have care responsibilities for example. This increases their risk of burnout and could also have a negative effect on their other employment and home life, differing from leaders who are solely employed by the church.

The research into burnout in church leadership has not yet been extended to look at leaders below senior leadership, providing the sample group for this research to focus on. As their roles might be different to senior leadership, part of this research aimed to understand the nature of their leadership roles and specific pressures they faced to see if there were any differences across the leadership levels.

Well-Being

Little research has been conducted with leaders at different levels in the church and how expectations of leadership can impact their well-being.

Well-being is defined as “the state of being comfortable, healthy or happy” in the Oxford Dictionary (2018) with the World Health Organisation (2014) adding that it can include being able to contribute to the community, work productively and fruitfully, and cope with the normal stresses of life. It encompasses the whole person, and everyone experiences well-being, whether positive or negative, on a daily basis.

To help quantify well-being, psychologists have created models, within which elements can be measured to provide an indication of the quality of well-being at a given time. One of the more widely accessible models is Martin Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model which states we need positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, sense of meaning and accomplishment in order to flourish and have positive well-being. Another commonly used model is Ryff’s scale of psychological well-being (1989) outlining self-acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life and personal growth as criteria for positive well-being. There are other models which have similar criteria but may also include justice and religion or spirituality (37). For every model, if one or more area is lacking then there is increased risk for low well-being and mental health difficulties.

Three criteria overlap when assessing well-being and burnout; relationships, meaning in life or purpose, and accomplishment or achievement (23; 26; 37). If an individual is starting to question or lose their sense of purpose in a role, this could be linked to the beginnings of emotional exhaustion – feeling drained of energy and motivation to keep going. Being emotionally exhausted can then impact on relationships, causing strain and detachment, and a lower the sense of accomplishment or self-efficacy (14). Not only does a lack in these three areas indicate a potential for low well-being, but it starts to identify risk factors in the areas of workload, reward, community and fairness within burnout (14; 15). Not all church leaders will have experienced burnout, but by understanding a church leader’s sense of their own well-being and what they think impacts it; this research aimed to understand how they maintained well-being and what practices were in place that could prevent low well-being and burnout.

From this review of the literature, it is clear to see that being a leader in a church is different compared to leading in another organisation. Biblical teaching provides a foundation from which leadership may be a calling to serve God and the Church, as well as a way of life. Well-being and burnout are closely linked but have not yet been well researched beyond senior church leaders. This research aimed to build on the research of Chandler (2008, 2010) and Frederick et al. (2018) through similar research methods. The main questions focused around understanding the pressures and expectations faced by church leaders, their experience of well-being in their role, and how positive well-being was promoted. To best achieve this aim, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as a qualitative approach focused on experiences and meaning (21; 28).

Method

I created a questionnaire that was sent out on social media, with 22 church leaders completing before the deadline. Participants were aged from 20 to 63 years, with 77% being under the age of 35. The length of ministry ranged from 1-20 years, with 77% serving for 5 years or less in their leadership role. There was a good mix of leaders involved in ministry areas ranging from compassion to sound and technology.

Analysis and Discussion

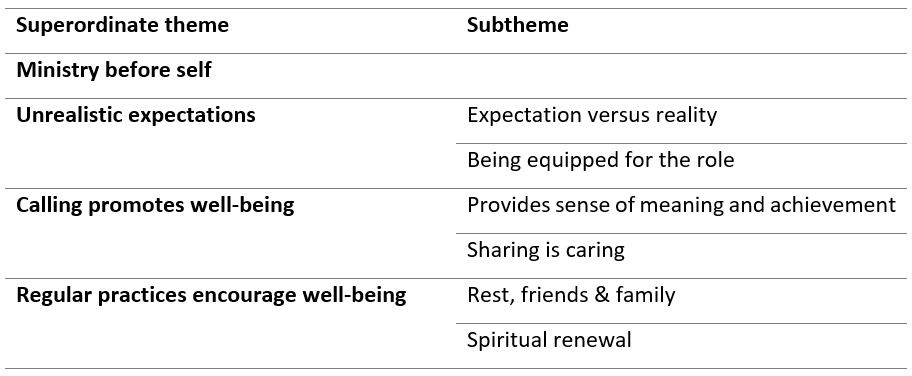

Table 2 shows the final themes and provides a structure for the following discussion. As shown in Table 1., Leaders are assigned a number from 1 to 22 to maintain their anonymity, but no other changes have been made to their words as the data provided was not revealing of participants’ identities.

Ministry before self

One of the main expectations that leaders face is putting their ministry area above any other commitments, even when they are not leading. Many of the leaders described feeling that they had to be and do everything, often to the detriment of their personal life. Leader 4, who is paid for some of her hours in pastoral care and small groups, wrote that she was “Always feeling "on duty" so unable to fully engage in services”. Other leaders voiced similar frustration in their ministry area feeling as though “I don’t work enough” and that “sticking to my hours …makes me look uncommitted”. Here, Leader 3 points to underlying feelings of shame or guilt that may fuel the need for many of the leaders to work more than they must.

Leader 6, a voluntary youth leader, wrote:

“Normal life/church life balance regularly suffers, expected to be involved in everything without the understanding that family life prevents doing that, and that there needs to be time to rest on a regular basis.”

Leader 15, who is the music ministry lead and part of the church council, wrote:

“There's also the pressures of time and energy: I often lead the band in church twice on a Sunday, which totals to about 5-6 hours including practice and service time, and it's a role that is physically and emotionally demanding.”

This expectation to be present in church and fit everything in was also noted by seven other leaders, most of whom served in a voluntary capacity. Their data also alluded to this feeling of sacrifice, and potential unjustness of not getting rest or time with family, that accompanies leadership. This has then influenced their emotional health and ability to deal with difficult situations. It appears that some of the leaders expect themselves to be able to prioritise their time well, rather than it be an expectation set by the church:

“I often have to switch priorities from a day today [sic] all week to week basis and sometimes feel like I am doing the church a disservice as my salary is paid for by the congregations [sic] tithes And [sic] that sometimes brings a little extra pressure to get certain things done” – Leader 22.

Here, Leader 22 seems to put upon himself the expectation of utilising his time well, so that the church gets good value for money on the hours that he is paid for. It may be that his church’s income is small and so there is an unspoken expectation that he must show he is being wise with what he has been given. Church leaders are expected to be above reproach, as described in Titus and 1 Timothy, leading in an ethical and conscientious manner. This concept of doing a “disservice” and wanting “to get certain things done” may come from emulating other leaders who act in an ethical way. If they have other leaders around them who demonstrate high levels of conscientiousness, research suggests that this is internalised and reciprocated (34). It could be that by having to change priorities, Leader 22 is not always able to lead the highest standard they want to, leading to this perceived sense of disappointment from the congregation.

It also seems that there are other expectations, particularly noted by leaders in youth ministry or small groups, around meeting up or being free outside of their usual hours.

“some people do not realise that you work FT [full-time] as well and cannot be available during work time to meet their needs….I have struggled with criticism of my availability as a small group leader outside of the normal small group times (midweek meeting time, Sundays, occasional evenings) ie during my paid working day.” – Leader 13

This expectation of having extra time outside of ministry hours seems to come from those that are engaging with the ministry area. Chandler (2010) found that leaders can find it hard to say no, stemming from a fear of being rejected or wanting to be a good role model. This is emulated by Leader 13 who although does not appear to fear rejection, the people in her small group may have felt rejected by her lack of time for them. Leader 10 seems to share a similar view to meeting up with “the youth when they need/want to” outside of the usual sessions. Leaders may fear rejection from their congregation, but there also seems to be a sense of not wanting to appear like they have rejected the congregation. This could be because there is a perceived lack of social support on either side of the relationship if someone does not have additional time available, increasing the fear of rejection. It may be that as Christians highly value relationships and acceptance, research by Langens and Schüler (2005) suggest they are more likely to avoid rejection. Therefore, leaders could potentially feel more anxious or insecure in social situations, such as leading a small group or meeting up with young people, where there is already “criticism of my availability” or other tensions in the relationship.

Unrealistic expectations

Expectations versus reality

Particularly with leaders who volunteer, there seems to be a disparity with what is expected of them and what they think they can realistically do. Leader 16 writes that his congregation do not know “the whole truth of what church leadership is and having [sic] a warped, individualistic view of what it could be.” Leader 17 emulates this, adding that it is not just the congregations who have unrealistic expectations but “Having overbearing [sic] higher powers. If your own leader has unrealistic expectations upon you, it can effect [sic] your leadership.”

Both leaders’ experiences point to a lack of understanding from the congregation of what ministry leaders can do, which is reflected by senior leadership. However, apart from small group Leader 13, this experience of expectations seems exclusive to the youth ministry. Perhaps this reflects differing demands from the young people and their parents as they journey through adolescence. Young people are developing their own faith and independence, with peers becoming more influential in decision making, but parents still have high levels of involvement and ‘parental responsibility’ (25).

Leader 5, paid in children’s and youth ministry, summed this up by writing:

“There's pressure to make a lot of different people happy: children, their parents, the teams, the schools, the church leadership, and lastly, you. You can never make everyone happy but every one [sic] expects it.”

It may be that leaders in children’s and youth ministry perceive a greater level of expectation due to the number of stakeholders involved. Whereas other ministry areas, such as worship, may be more narrowly focused towards the adult members of the congregation, working with young people does not stop there. It includes their parents, carers, other team members, who may all have different expectations, some of which may not always amalgamate. It could be possible that being conscientious of everyone’s needs leads to some fear of rejection if tensions arise because they cannot all be met (11; 34).

Being equipped for the role

Youth ministry is also the main area where leaders express an expectation of having the right knowledge and skills to do the role. When writing about the pressures they face, Youth Leader 21 wrote:

“Knowing the right thing to say! Dealing with more sensitive issues young people face today, social media, pornography, sex and relationships. I don't always feel equipped to do that. The young people are growing up in a very different time to when I was a teenager. Social media has changed things as well as the internet in general. I haven't personally experienced a lot of the challenges they face.”

Leaders 1 and 16, who were aged 25 and over, expressed similar pressures. Although not the oldest leader to take part in this research, Leader 21 was one of the oldest youth leaders. Younger youth leaders may not have mentioned this type of pressure as they have more recent experience of being a teenager and may have younger siblings or family members. Or, it could be that other expectations were more pressing at the time of participating in this research. For older youth leaders it might be that their ministry time is their only current experience working with young people and seeing the challenges they face. This could explain the anxiety felt by Leader 21, as adolescence is a crucial developmental stage in developing positive habits which could relate to “social media, pornography, sex and relationships”. Research suggests that young people are more likely to engage in risky behaviours, increasing the importance of positive role models, which may add to the expectation of “Knowing the right thing to say” (25).

Most of the leaders show signs of “Working at over capacity” (Leader 7) and not always having the time and energy for the demands of their ministry area and other family or social commitments. This is indicative of emotional exhaustion, with potential to be at risk in the areas of workload and community (14; 15). 16 out of the 22 leaders said that they had experienced low well-being due to their role, which could be in part due to the emotional exhaustion brought on by feeling they are not doing enough, or there is not enough time to do everything. Lacking time with family and friends appears to be a product of being a leader, which could lead to low well-being, lowering their ability to then cope and adapt to changes in their role (23; 26; 37; 38). This mirrors experiences of senior leaders prior to burnout, suggesting that burnout is not exclusive to this group, but could be a phenomenon more widely experienced across Church leadership (5; 6).

Calling promotes well-being

Provides sense of meaning and achievement

For almost all the leaders, enjoyment came from being with others and being on a collective journey of faith. Around half of the leaders expressed getting a sense of meaning and achievement or fulfilment out of their role. For Leader 11 and five other leaders, leadership is not just about leading, but serving God and the Church through their role.

“I enjoy being able to help people and encourage people in their faith. I find it fulfilling when you see God's promises fulfilled and prayers answered and are able to share that with others” – Leader 11

Clary et al. (1998) identified six functions of volunteering: expressing values around concern for others, opportunity for new learning experiences, to engage in social groups, preparing for or maintaining career-based skills, preventing negative feelings, enhance self-development and growth. Although some of these functions may be present, motivations stem from the leader’s faith, seeing “God’s promises fulfilled and prayers answered”, and could be described as a calling on life. They are not leading to enhance their own careers or self-development, but to enhance the work of the church locally and nationally, so people can grow in faith.

Sharing is caring

As well as finding a purpose, leaders also gain satisfaction from sharing their skills with others and giving back to the community. This is shown in a response from Leader 10, who write:

“Personally [sic] I feel as though I was helped so much by my youth leaders when I was at their age and would be gutted if they missed out on that opportunity too. I enjoy the sound team work I do as music is my passion and my job and helping others to worship is such a satisfying feeling.”

This almost seems to tilt the Functionalist Approach on its head, as it is not just for the benefit of the leaders, but so they can help others (8). Some of the other leaders expressed a similar joy watching their youth grow and develop or see members of the congregation strengthen their faith through engagement with that leader’s ministry area.

For many of the leaders who participated in this research, despite the high demand leading in ministry has on time and energy, this is often outweighed by the feeling of doing God’s work and building His community. Leader 16 wrote:

“I have had periods of time when I have considered leaving due to the stress and pressure but I have always (so far) been able to see the bigger picture and find that I still believe it is worth it in the end…Being able to watch as something you have helped facilitate is breathed into by the Holy Spirit and people connect with him. That is a privilege and a huge blessing.”

It may be that their faith gives them an optimism which reduces the effects of the “stress and pressure” enough to be able to see the worth in the work that they are doing and strengthen their meaning in life (22). It could also be that volunteering in the church where they practice their faith creates a stronger identification with the people who engage with their ministry and provides the internal resources to cope and “see the bigger picture” (29). Where workload and community may become strained and be a risk to lowering the well-being of church leaders, the strength of a sense of calling may help maintain a positive balance.

Regular practices encourage well-being

Rest, friends & family

At least 9 of the leaders write that a couple of ways to promote well-being are that they make sure to “rest well” (Leader 15) and “Spend time with friends and family” (Leader 21). Senior leaders stated that taking time to rest and be around a supportive community aided in their recovery from burnout and became a higher priority when back in leadership (6). Serving at church normally occurs during a Sunday, or in an evening, when one would normally have time to rest and spend with family outside of standard working hours. Helliwell and Wang (2014) found that the extra time gained at the weekend to spend with friends and family increased the average happiness in their participants. This could explain why many leaders raised it as a pressure as well as a positive factor when writing about their leadership role. If their ministry time is mostly during evenings and weekends, it can impact on free time spent with family or friends potentially lowering their well-being and increasing risk for burnout. However, the time that they do get to spend resting and being around others, can increase positive emotions which is a core element of positive well-being (Helliwell et al., 2014; 26; 37).

Spiritual Renewal

Over half of the leaders included a spiritual element in their definition of well-being, with many of these listing spiritual practices such as “prayer”, “sabbath” and “worship” as beneficial to their well-being. Research into religious or spiritual well-being has suggested that it should be considered as an important personality trait when looking at well-being from a psychological perspective. When religious or spiritual well-being is high, it is positively correlated with different areas of psychological well-being (32). Christians believe in the teachings of Jesus Christ who, throughout the Gospels, taught his disciples to pray, fast and partake in what is now known as The Last Supper or Holy Communion. It is these and other practices that Christians are encouraged to partake in regularly, so that they may strengthen their faith and be renewed by the Holy Spirit. This could explain why these leaders, and other leaders in the Church, have noted spiritual practices as beneficial to their well-being (5; 6; 10). The Christian faith is where they find and engage with community and develop a meaning and purpose in life. This suggests that faith is the foundation from which other criteria for well-being can be met.

Rest, spending time with friends and family and spiritual renewal are equally discussed by the leaders who participated in this research, which is similar to the conclusions drawn by other researchers (5; 6; 10). Across the board, it is not just one of these practices which promotes well-being, but a combination of these and others which are used.

Conclusion

This research aimed to understand the experiences of church leaders across different levels of the church. Specifically, it focused on the pressures and expectations faced in their leadership role and the impact this may have on their well-being.

Expectations in church leadership are rooted in biblical teachings. These teachings describe not only a way of leading that values putting others first, but also a way of life. Leaders in the church must accept and show a commitment to the teachings of the Bible in order hold this position. This made them a unique group to explore for research compared to leaders in other organisations.

Previous research found that senior church leaders were likely to experience burnout due a variety of factors. These include high demands from their ministry area, and a lack of time spent in rest, support networks and spiritual renewal (5; 6; 10). Research did not specifically look at leaders below senior leadership, which was the sample group chosen for this research. Links were drawn between risk factors for burnout and models of well-being, such as emotional exhaustion impacting on relationships and sense of achievement (14). This suggested that if church leaders were to experience low well-being, they would be at risk of burnout. As not all church leaders may have experienced burnout, well-being became the focus alongside leadership expectations.

Four superordinate themes emerged, with 6 related subthemes, from the analysis of data obtained through online questionnaires using IPA. Many of the leaders found that they were expected to put ‘Ministry before self’ and felt that they needed to be working more hours or do more with their time. Along with ‘Unrealistic expectations’ experienced by trying to please their church, the data started to suggest that being in church leadership was detrimental to their sense of well-being. It could be possible that leading in the church comes with high levels of conscientiousness, such as wanting to get the most out of their hours, which is reinforced by biblical teachings and church role models. This in turn may increase anxiety and fear of rejection when engaging with others within the ministry, negatively impacting on well-being too (11; 34).

Unexpectedly, this increased risk for burnout appeared to be outweighed by the sense of meaning and achievement gained through leadership. For many of the participants, becoming a leader came out of a sense of calling - to serve God and His people. This calling provides a purpose in their life, with many reporting high life-satisfaction from helping people on their journey of faith and seeing good works come out of their ministry. Even in difficult times during ministry, seeing the positive impact their work has on others improved their sense of well-being. The balance appeared to come from the ability to take part in regular practices that encourage well-being. Time to engage in practices such as prayer, rest-taking, spiritual renewal and having time with family and friends were crucial to promoting positive well-being, as shown in previous research (5; 6; 10). Yet, when spare time is sacrificed to high demands from ministry, leaders are more likely to tip into the onset of burnout, as seen in the cases of senior leaders (6).

Although further research could look at this topic with a different approach, potentially generating more generalisable results, this research poses some important points for reflection. Leadership at all levels of the Church may experience low well-being and potentially burnout due to high or unrealistic expectations and demands from ministry. This can diminish the time available for spiritual renewal, which is vital to the faith of Christian leaders and the sense of calling they have. In order to prevent leaders from burning out, it is important for churches to consider expectations and well-being. This could include reviewing how they support and promote practices that improve well-being, and better manage the expectations of leaders and the congregation.

References

- Breakwell, G. M. (2012). Interviewing. In G. M. Breakwell, J. A. Smith & D. B. Wright (Eds.), Research Methods in Psychology (4thed., pp.439-460). London: SAGE.

- 2. British Psychological Society. (2009). Code of Ethics and Conduct. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

- British Psychological Society. (2017). Ethics Guidelines for Internet-mediated Research. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

- Catano, V. M., Pond, M. & Kelloway, E. K. (2001) Exploring commitment and leadership in volunteer organisations. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22, (6), 256-263.

- Chandler, D. J. (2008). Pastoral Burnout and the Impact of Personal Spiritual Renewal, Rest-taking, and Support System Practices. Pastoral Psychology, 58, (3), 273-287.

- Chandler, D. J. (2010). The Impact of Pastors’ Spiritual Practices on Burnout. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 64, (2) doi/10.1177/154230501006400206

- The Church of England. (n.d.) Understanding selection. Retrieved August 3, 2018, from https://www.churchofengland.org/life-events/vocations/preparing-ordained-ministry/understanding-selection

- Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen J. & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and Assessing the Motivations of Volunteers: A Functional Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, (6), 1516-1530.

- Fife-Schaw, C. (2012). Questionnaire Design. In G. M. Breakwell, J. A. Smith & D. B. Wright (Eds.), Research Methods in Psychology (4th ed., pp.439-460). London: SAGE.

- Frederick, T. V., Dunbar, S. & Thai, Y. (2018). Burnout in Christian Perspective. Pastoral Psychology, 67, (3), 267-276.

- Langens, T. A. & Schüler, J. (2005). Written Emotional Expression and Emotional Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Fear of Rejection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, (6), 818-830.

- Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., & Friedman, H. (Ed.) (1998). Encyclopaedia of mental health, New York: Academic Press.

- Malphurs, A. & Mancini, W. (2003). Building Leaders: Blueprints for developing leadership at every level of your church. Michigan: Baker Books.

- Maslach, C. (2000). A multidimensional theory of burnout. In C. S. Cooper (Ed.), Theories of Organisational Stress. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 68-85.

- Maslach, C. & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Ealy predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93 (3), 498-512.

- McMillan, R. C. (2014) The Next Gen Leader. Pompton Planis, N.J.: Career Press.

- The Methodist Church. (n.d.) The President and Vice President. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from http://www.methodist.org.uk/about-us/the-methodist-church/structure/the-president-and-vice-president/

- The Methodist Church. (2016). The Methodist Church in Britain: Its Structure and Organisation. Retrieved July 8, 2018 from http://www.methodist.org.uk/media/4537/whoweare-mcstructure-0716.pdf

- Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. (2nd ed.). California: SAGE Publications.

- Moran, M., Flannelly, K. J. Weaver, A. J., Overvold, J. A, Hess, W. & Wilson, J. C. (2005). A Study of Pastoral Care, Referral, and Consultation Practices Among Clergy in Four Settings in the New York City Area. Pastoral Psychology, 53, (3), 255-266.

- Pietkiewicz, I. & Smith, J.A. (2012) Praktyczny przewodnik interpretacyjnej analizy fenomenologicznej w badaniach jakościowych w psychologii. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 18(2), 361-369.

- Plante, T. G., Yancey, S., Sherman, A. & Guertin, M. (2000) The Association between strength of religious faith and Psychological Functioning. Pastoral Psychology, 48, (5), 405-412.

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 6, 1069-1081.

- Samaritans. (2018). Volunteer with us. Retrieved August 3, 2018 from https://www.samaritans.org/volunteer-us

- Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger L. H., Blakemore, S.-J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A. C. & Putton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A Foundation for Future Health. The Lancet, 379, 1630-1640.

- Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish. New York: Free Press.

- Schneider, S. K. & George, W. M. (2011). Servant Leadership versus transformational leadership in voluntary service organisations. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 32, (1), 60-77.

- Smith, J. A. & Eatough, V. (2012). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In G. M. Breakwell, J. A. Smith & D. B. Wright (Eds.), Research Methods in Psychology (4th ed., pp.439-460). London: SAGE.

- Thoits, P. A. & Hewitt, L. N. (2001) Volunteer Work and Well-Being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, (2), 115-131.

- a. Trent Vineyard. (2018). Potential Leaders Training. Nottingham: Trent Vineyard.

- b. Trent Vineyard. (2018). Get in touch and meet our team. Retrieved July 8, 2018 from https://trentvineyard.org/get-in-touch/

- Unterrainer, H.-F., Ladenhauf, K. H., Moazedi, M., L., Wallner-Liebmann, S. J. & Fink, A., (2010). Dimensions of Religious/Spiritual Well-Being and their relation to Personality and Psychological Well-Being. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, (3), 192-197.

- Vaters, K. (2016, September 13). Epidemic: Another Pastor Burned Out and Quit Last Sunday. Christianity Today. Retrieved July 9, 2018 from https://www.christianitytoday.com/karl-vaters/2016/september/epidemic-another-pastor-burned-out-and-quit-last-sunday.html?start=1

- Walumbwa, F. O., Morrison, E. W. & Christensen, A. L. (2012). Ethical leadership and group in-role performance: The mediating roles of group conscientiousness and group voice. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, (5), 953-964.

- Weiss, M., Razinskas, S., Backmann, J. & Hoegl, M. (2018). Authentic Leadership and leaders’ mental well-being: An experience sampling study. The Leadership Quarterly, 29, (2), 309-321.

- Well-being. (n.d.). In OxfordDictionairies.com. Retrieved August 2, 2018 from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/well-being

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 111-140. (Appendix C).

- World Health Organisation. (2014, August). Mental health: a state of well-being. Retrieved August 2, 2018 from http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/